Don’t Be So Nosey

When we go see a big blockbuster movie, it is a pleasurable assault on three of our five senses. Our eyes dart across the screen as our hero dashes forward. Our ears pick up the Doppler effect of sound bouncing around us. Our bodies feel the deep base of rumbling anticipation.

What about taste and smell? Well there is the butter of popcorn and syrupy sweet soda to keep our mouths satisfied, but there are rarely things in a movie that I’d want to taste. But, what about smells, what about enjoying the smell of car exhaust and burning wood … um … I mean napalm in the morning? Or the smell of hot coffee and pancakes …

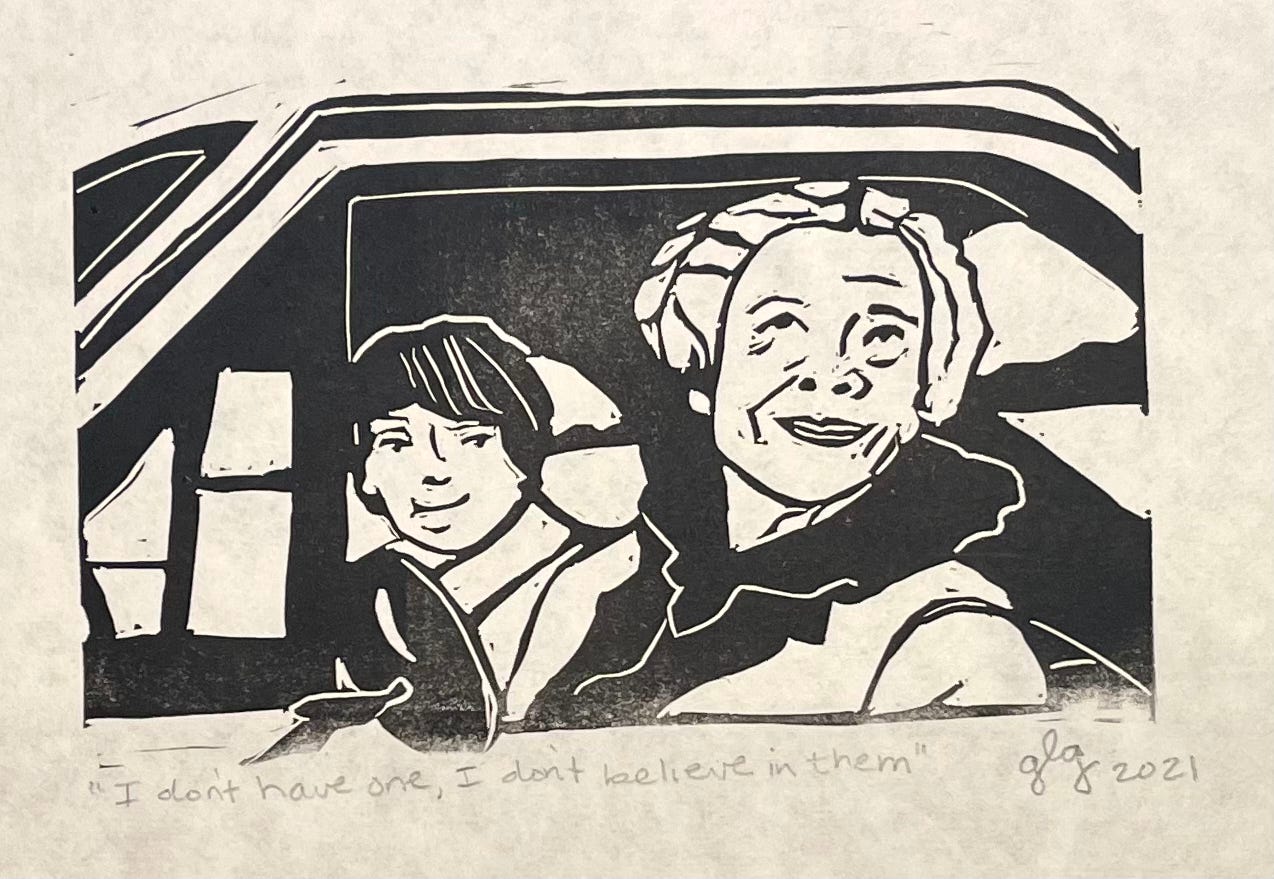

This would make a cool cover for my Rom-Com Novella, ‘Tomorrow May Be Too Late’

When you think about it, the nose is often left out at the movies. But that is not for a lack of trying. And in this edition of Rabbit Hole of Research we’re going to get nosey!

If You Smelt It, You Dealt It

So, you may be wondering how I got down this Rabbit Hole. There is a scene in the classic movie ‘Harold and Maude’ where Maude shows Harold her “odorifics” machine, or what seems to be a kind of tape-recorder of smells. Maude gives Harold a face-mask attached to a tube that runs from the machine, which he begins cranking, sniffing, and describing the smells: subway, perfume, cigarettes, and even the scent of snow. Then a few weeks later I was reading ‘The Veldt’ by Ray Bradbury; the virtual environment had ‘odorophonic’ technology to engage the olfactory—And this got me thinking, “Is a smell machine possible? Or is it all Handwavium?” Down the Rabbit Hole we go.

Fake it until you make it

So, I want to take a step back and talk about all the senses and how they work; and why smell is tricky to reproduce:

Sight: When light hits the retina (a light-sensitive layer of tissue at the back of the eye), special cells called photoreceptors turn the light into electrical signals. These electrical signals travel from the retina through the optic nerve to the brain. Then the brain turns the signals into the images you see.

Hearing: Sound waves enter the outer ear and travel through a narrow passageway called the ear canal, which leads to the eardrum. The eardrum vibrates from the incoming sound waves and sends these vibrations to three tiny bones in the middle ear. These bones are called the malleus, incus, and stapes which translate the sound waveform into electrical signal your brain can interrupt.

Touch: Sensations begin as signals generated by touch receptors in your skin and converted to electrical signals. These signals travel along sensory nerves made up of bundled fibers that connect to neurons in the spinal cord. Then signals move to the thalamus, which relays information to the rest of the brain.

Smell/Taste: So, why am am I lumping taste and smell together? That’s because the sensation of taste starts with the molecules in the air around us that stimulate nerves in a small area located high in the nose. On the tongue, tastebud receptors detect sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami that stimulate the brain and affect the actual flavor of the foods we eat.

And when we smell something, our nose and brain work together to make sense of hundreds of very tiny invisible particles, molecules, that are floating in the air.

So, sight, hearing, and touch relies on converting a physical interaction or waveform into an electoral signal which your brain translates. You cannot represent smell as a waveform because the electrical impulses in your brain are unleashed by chemical receptors in your nose; depending on the molecules, floating in the air as you are sniffing, they will generate different kinds of electrical impulses, so your brain can identify it and provide useful information about it (if it is likely edible, or if you should avoid it).

Smell, not being a kind of radiation/waveform (like light) or vibration (like sound), but a bunch of molecules floating in the air, there's no waveform to represent and difficult to reproduce artificially.

Have you ever walked into a crowded elevator and yelled, “Molecule?”

Just because something is difficult doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to do it. So what if you don’t have a reproducible waveform that would generate the same reaction in your brain every time. All you have to do is figure out the molecules in the smell and blow that around and problem solved—and guess what, somebody did just that.

Smell-O-Vision was a system that released odor during the projection of a film so that the viewer could "smell" what was happening in the movie. The technique was created by Hans Laube and made its only appearance in the 1960 film Scent of Mystery, produced by Mike Todd Jr., son of film producer Mike Todd. It failed, New York Times review in 1960, Smell-O-Vision was deemed an ineffectual stunt: “The odor squirters are mildly and randomly used,” wrote the paper, “and patrons sit there sniffing and snuffling like a lot of bird dogs trying hard to catch the scent.”

Aromarama was a rival system, but suffered from the same short comings of the Smell O Vision, and just faded away.

Maybe this technology was just ahead of its time, what fails then will surely succeed next time.

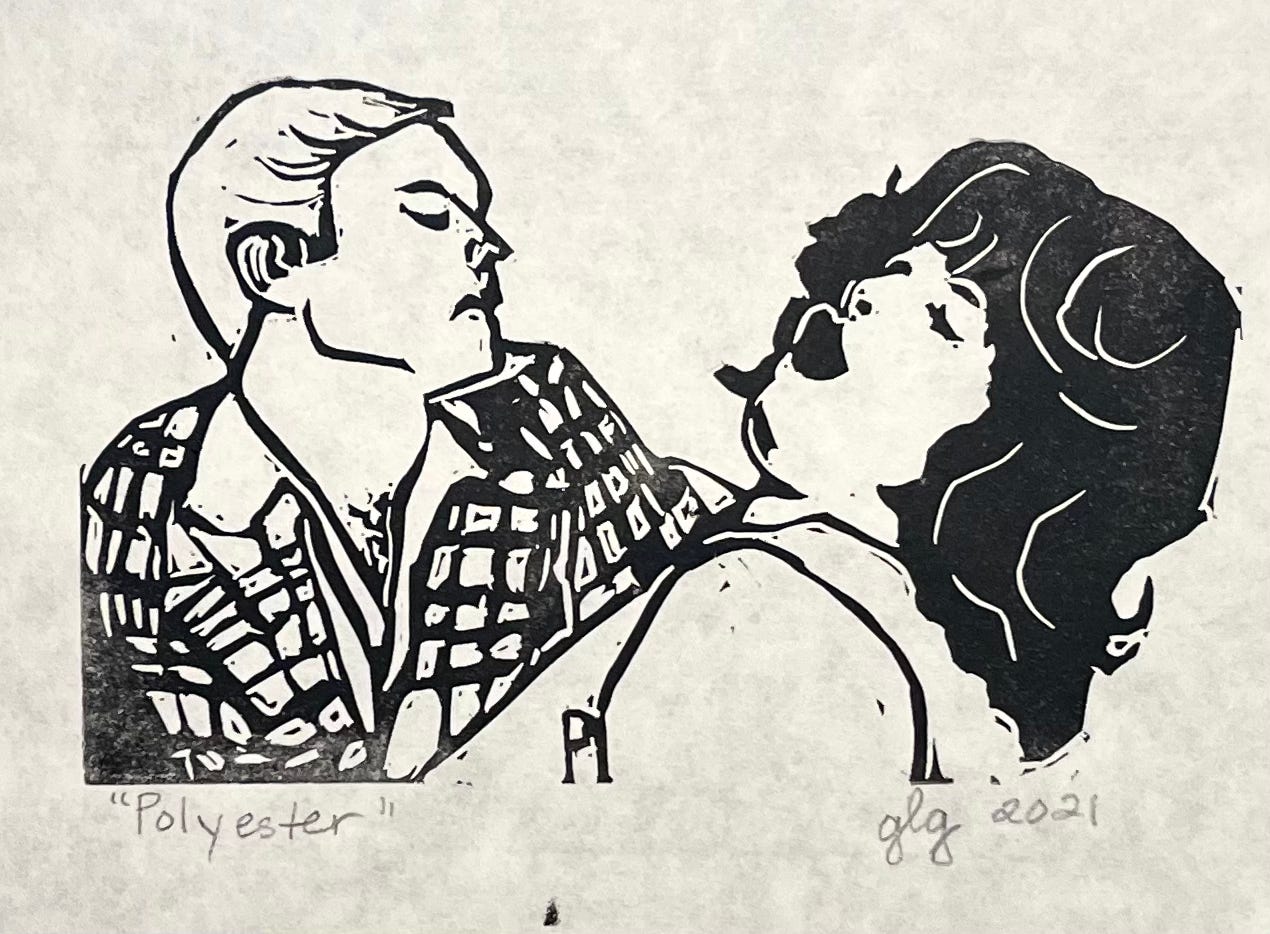

The filmmaker John Waters tried scratch and sniff cards to accompany his movie Polyester in the early 1980s, but no other filmmaker copied his gimmick and maybe for good reasons (time to smell the ‘poop’—Yes, poop was one of the smells on the card).

To make fake smells maybe we need ‘fake noses’, and I’m not talking about the cosmetic surgery craze of the 80’s, but the research conducted to develop technologies, commonly referred to as electronic noses, that could detect and recognize odors and flavors. The idea was to have a machine that could analyze a smell and tell you how to reproduce it. Even though the electronic noses worked, kind of, the thing often overlooked with technology is real noses are different. The problem is that smell is complicated—many molecules have to be interpreted by real noses, cultural perceptions of these molecules (a rose by any other name may smell like crap.)

Can you smell what the Handwavium is cooking?

A good idea is hard to kill like Steven Seagal and people are still trying to make smells a part of the immersive TV/movie experience. The future of this technology seems to be bypassing using complex ‘fake nose’ interpreted scent molecules and directly stimulating the olfactory with electrodes, and convincing the brain that you are smelling something.

So, in the future you may have to stuff electrodes up your nose if you want to experience ‘The Veldt’, like in Ray Bradbury’s short story, or the fresh scent of snow in summer that Maude is cranking out. And you thought the Covid-test brain poke was bad. Sad to say that fake smell technology is mostly Handwavium, but one day coming to a theater near you … until next time, stay smelly my friends!

Hope you enjoyed this little trip down my Rabbit Hole of Research, and will join me next time as I reveal the actual factual science in fiction and fantasy.

If you missed an episode, you can find them here. Like the prints you see in my newsletter, they are done by the talented Georgia Geis and the prints will be available for purchase at atomicnumber14.com.

Did I get something wrong ... right ... wanna say hello? Let me know, I write back, tell me your favorite smell, anything— Email me

If you want to chat with me on the interwebs, find me at your favorite digital hangout!

Don’t Be So Nosey

When we go see a big blockbuster movie, it is a pleasurable assault on three of our five senses. Our eyes dart across the screen as our hero dashes forward. Our ears pick up the Doppler effect of sound bouncing around us. Our bodies feel the deep base of rumbling anticipation.

What about taste and smell? Well there is the butter of popcorn and syrupy sweet soda to keep our mouths satisfied, but there are rarely things in a movie that I’d want to taste. But, what about smells, what about enjoying the smell of car exhaust and burning wood … um … I mean napalm in the morning? Or the smell of hot coffee and pancakes …

Print by Georgia Geis @atomicnumber14

This would make a cool cover for my Rom-Com Novella, ‘Tomorrow May Be Too Late’

When you think about it, the nose is often left out at the movies. But that is not for a lack of trying. And in this edition of Rabbit Hole of Research we’re going to get nosey!

If You Smelt It, You Dealt It

So, you may be wondering how I got down this Rabbit Hole. There is a scene in the classic movie ‘Harold and Maude’ where Maude shows Harold her “odorifics” machine, or what seems to be a kind of tape-recorder of smells. Maude gives Harold a face-mask attached to a tube that runs from the machine, which he begins cranking, sniffing, and describing the smells: subway, perfume, cigarettes, and even the scent of snow. Then a few weeks later I was reading ‘The Veldt’ by Ray Bradbury; the virtual environment had ‘odorophonic’ technology to engage the olfactory—And this got me thinking, “Is a smell machine possible? Or is it all Handwavium?” Down the Rabbit Hole we go.

Print by Georgia Geis @atomicnumber14

Fake it until you make it

So, I want to take a step back and talk about all the senses and how they work; and why smell is tricky to reproduce:

Sight: When light hits the retina (a light-sensitive layer of tissue at the back of the eye), special cells called photoreceptors turn the light into electrical signals. These electrical signals travel from the retina through the optic nerve to the brain. Then the brain turns the signals into the images you see.

Hearing: Sound waves enter the outer ear and travel through a narrow passageway called the ear canal, which leads to the eardrum. The eardrum vibrates from the incoming sound waves and sends these vibrations to three tiny bones in the middle ear. These bones are called the malleus, incus, and stapes which translate the sound waveform into electrical signal your brain can interrupt.

Touch: Sensations begin as signals generated by touch receptors in your skin and converted to electrical signals. These signals travel along sensory nerves made up of bundled fibers that connect to neurons in the spinal cord. Then signals move to the thalamus, which relays information to the rest of the brain.

Smell/Taste: So, why am am I lumping taste and smell together? That’s because the sensation of taste starts with the molecules in the air around us that stimulate nerves in a small area located high in the nose. On the tongue, tastebud receptors detect sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami that stimulate the brain and affect the actual flavor of the foods we eat.

And when we smell something, our nose and brain work together to make sense of hundreds of very tiny invisible particles, molecules, that are floating in the air.

So, sight, hearing, and touch relies on converting a physical interaction or waveform into an electoral signal which your brain translates. You cannot represent smell as a waveform because the electrical impulses in your brain are unleashed by chemical receptors in your nose; depending on the molecules, floating in the air as you are sniffing, they will generate different kinds of electrical impulses, so your brain can identify it and provide useful information about it (if it is likely edible, or if you should avoid it).

Smell, not being a kind of radiation/waveform (like light) or vibration (like sound), but a bunch of molecules floating in the air, there's no waveform to represent and difficult to reproduce artificially.

Have you ever walked into a crowded elevator and yelled, “Molecule?”

Just because something is difficult doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to do it. So what if you don’t have a reproducible waveform that would generate the same reaction in your brain every time. All you have to do is figure out the molecules in the smell and blow that around and problem solved—and guess what, somebody did just that.

Smell-O-Vision was a system that released odor during the projection of a film so that the viewer could "smell" what was happening in the movie. The technique was created by Hans Laube and made its only appearance in the 1960 film Scent of Mystery, produced by Mike Todd Jr., son of film producer Mike Todd. It failed, New York Times review in 1960, Smell-O-Vision was deemed an ineffectual stunt: “The odor squirters are mildly and randomly used,” wrote the paper, “and patrons sit there sniffing and snuffling like a lot of bird dogs trying hard to catch the scent.”

Aromarama was a rival system, but suffered from the same short comings of the Smell O Vision, and just faded away.

Maybe this technology was just ahead of its time, what fails then will surely succeed next time.

The filmmaker John Waters tried scratch and sniff cards to accompany his movie Polyester in the early 1980s, but no other filmmaker copied his gimmick and maybe for good reasons (time to smell the ‘poop’—Yes, poop was one of the smells on the card).

Print by Georgia Geis @atomicnumber14

To make fake smells maybe we need ‘fake noses’, and I’m not talking about the cosmetic surgery craze of the 80’s, but the research conducted to develop technologies, commonly referred to as electronic noses, that could detect and recognize odors and flavors. The idea was to have a machine that could analyze a smell and tell you how to reproduce it. Even though the electronic noses worked, kind of, the thing often overlooked with technology is real noses are different. The problem is that smell is complicated—many molecules have to be interpreted by real noses, cultural perceptions of these molecules (a rose by any other name may smell like crap.)

Can you smell what the Handwavium is cooking?

A good idea is hard to kill like Steven Seagal and people are still trying to make smells a part of the immersive TV/movie experience. The future of this technology seems to be bypassing using complex ‘fake nose’ interpreted scent molecules and directly stimulating the olfactory with electrodes, and convincing the brain that you are smelling something.

So, in the future you may have to stuff electrodes up your nose if you want to experience ‘The Veldt’, like in Ray Bradbury’s short story, or the fresh scent of snow in summer that Maude is cranking out. And you thought the Covid-test brain poke was bad. Sad to say that fake smell technology is mostly Handwavium, but one day coming to a theater near you … until next time, stay smelly my friends!

Hope you enjoyed this little trip down my Rabbit Hole of Research, and will join me next time as I reveal the actual factual science in fiction and fantasy.

If you missed an episode, you can find them here. Like the prints you see in my newsletter, they are done by the talented Georgia Geis and the prints will be available for purchase at atomicnumber14.com.